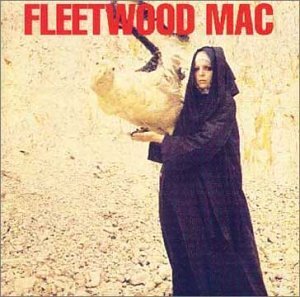

The Pious Birds of Good Omen

1. Need Your Love So Bad

2. Coming Home

3. Rambling Pony

4. The Big Boat

5. I Believe My Time Ain't Long

6. The Sun is Shining

7. Albatross

8. Black Magic Woman

9. Just the Blues

10.Jigsaw Puzzle Blues

11.Looking for Somebody

12.Stop Messin' Roung

Fleetwood Mac’s early discography is a tangled thicket of studio albums, singles, compilation LPs, and posthumous reissues—often indistinguishable except by catalogue number or sleeve art. The Pious Bird of Good Omen, released in 1969, is one such compilation, and yet, unlike many of its brethren, it earns its place in the canon. While ostensibly a collection of previously issued material, it features enough new or rare cuts to justify its status as a legitimate entry in the band's formative output.

The title, predictably obscure and vaguely mystical (apparently lifted from Coleridge’s Rime of the Ancient Mariner), gives little indication of the music contained within. But the content makes one thing abundantly clear: Peter Green was not just the leader of Fleetwood Mac—he was its very essence.

Opening with a glorious cover of Little Willie John’s Need Your Love So Bad, the album immediately signals a change in tone. This isn’t the raucous, amp-crackling blues of their first LP. This is something smoother, more refined—complete with (yes) a string section that manages to enhance rather than clutter. Green’s vocal delivery here is nothing short of sublime. He never pushes. He pleads. He floats. It is the sound of blues evolving into something soulful, delicate, and distinctly British.

The compilation also marks the arrival of Danny Kirwan, the band’s third guitarist and soon-to-be central figure in their transitional years. Though his initial contributions are modest in length, they are hardly insignificant. Jigsaw Puzzle Blues, a brief, twinkling instrumental clocking in under two minutes, hints at the melodic sensibilities Kirwan would later develop more fully. It's whimsical and oddly sophisticated—one of the album’s unexpected delights, and a tantalizing glimpse of things to come.

Elsewhere, Green continues to stretch the band’s stylistic boundaries. Albatross, a dreamy, wholly un-bluesy instrumental, feels more at home alongside the ambient meditations of late-60s psychedelia than in the smoky blues clubs of Soho. It floats along on a sea of tremolo guitar and wordless emotion, and became, somewhat astonishingly, a commercial success. There’s nothing else quite like it in the Mac’s catalogue—or anyone else's, really.

Then there’s Black Magic Woman, Green’s most enduring composition—though many listeners know it only through Santana’s fiery Latin reinterpretation. The original here is leaner, darker, and arguably more haunted. Green’s restrained vocal delivery and eerie phrasing imbue it with a sense of quiet menace that’s entirely his own. It remains one of the great blues songs of the era—its stature undiminished by decades of reinterpretation.

Other tracks (Rambling Pony, for instance) do less to push the envelope, but still serve as reminders of the group’s bluesy core. Spencer contributes his usual quota of Elmore James-style rave-ups, though by now the formula was showing signs of wear. In truth, much of the remainder of the album is a selection of B-sides and prior singles cobbled together, and one might fairly question the curation. With so much unreleased material in the vaults even at this early stage, the selections occasionally feel arbitrary.

Yet The Pious Bird of Good Omen holds together better than it has any right to. It captures a band on the cusp of transformation—still grounded in the blues but clearly itching to experiment, to expand, to evolve. Green’s songwriting had matured to the point where his pieces no longer merely imitated American idioms—they stood on their own as fresh, innovative, and uniquely his.

It may be filed under “compilation,” but to write off this record as mere filler would be a mistake. It offers some of the most affecting, forward-looking material the early Mac ever produced. Call it transitional, call it uneven—but don’t call it forgettable.

Go back to the main page

Go To Next Review